“Endings and beginnings sit so close to each other that it’s sometimes impossible to tell which is which.”

A soaring novel of love and grief from Printz Honor medal winner and National Book Award finalist Deb Caletti.

Nothing lasts forever, and no one gets that more than Tessa. After her mother died, it’s all Tessa can do to keep her friends, her boyfriend, and her happiness from slipping away. And then there’s her dad. He’s stuck in his own daze, and it’s so hard to feel like a family when their house no longer seems like a home.

Her father’s solution? An impromptu road trip that lands them in Tessa’s grandmother’s small coastal town. Despite all the warmth and beauty there, Tessa can’t help but feel even more lost.

Enter Henry Lark. He understands the relationships that matter. And more importantly, he understands her. A secret stands between them, but Tessa’s willing to do anything to bring them together—because Henry may just be her one chance at forever.

The Last Forever: The Seed Vault

My first view of the vault

I was just about to start work on my tenth YA novel titled, EVERYBODY’S HOME, when my husband showed me a picture. We were eating dinner, and he passed me his phone, where he’d opened an article about the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. There it was, an otherworldly image – a wedge of steel with a glowing window, stuck in ice with a backdrop of eerie blue. One look, and I was hooked. The image compelled me. I had to learn about it. No, I had to write about it. Just like that, poor EVERYBODY’S HOME was ditched, and I was speeding off with the new love of my life.

Book ideas are funny that way. They can be flashy, fickle, or nagging. But more than anything, when you find the right one, they say, This. Now.

A vault, hidden away in the farthest corner of the arctic, made for one, singular purpose: to store seeds so that civilization could start again in the event of a catastrophic event… This. Now. Also called the “Doomsday” Seed Vault, the vault is the world’s most critical treasure box, an iron and cement Noah’s Ark, which now houses nearly 800,000 different types of seeds (and three million individual ones) so that food production can be restarted anywhere on the planet following a global disaster.

View from the top. The window is actually an art installation, made of fibre-optic cables, mirrors and prisms. (Photo: The Independent)

I began my research right away. THE LAST FOREVER required a great deal of it, more than any of my books to date. It was one of my favorite parts of writing the book, because it led from surprise to surprise and from interesting fact to interesting fact. Yes, all that information about the seeds is true, as are the details about the vault, from the first lighting of the fuse that blasted open the frozen mountainside, to the sub-zero temperatures, to the many keys it takes to open the doors. The details about the nearest town, Longyearben, are also true: polar bears wander onto the streets, hungry and curious. You must wear a rifle outdoors. Reindeer wander through, as well. Transportation is by snow scooter. Whale might be on the dinner menu.

Longyearben. Warning! Polar Bear Crossing! (Photo: UNIS)

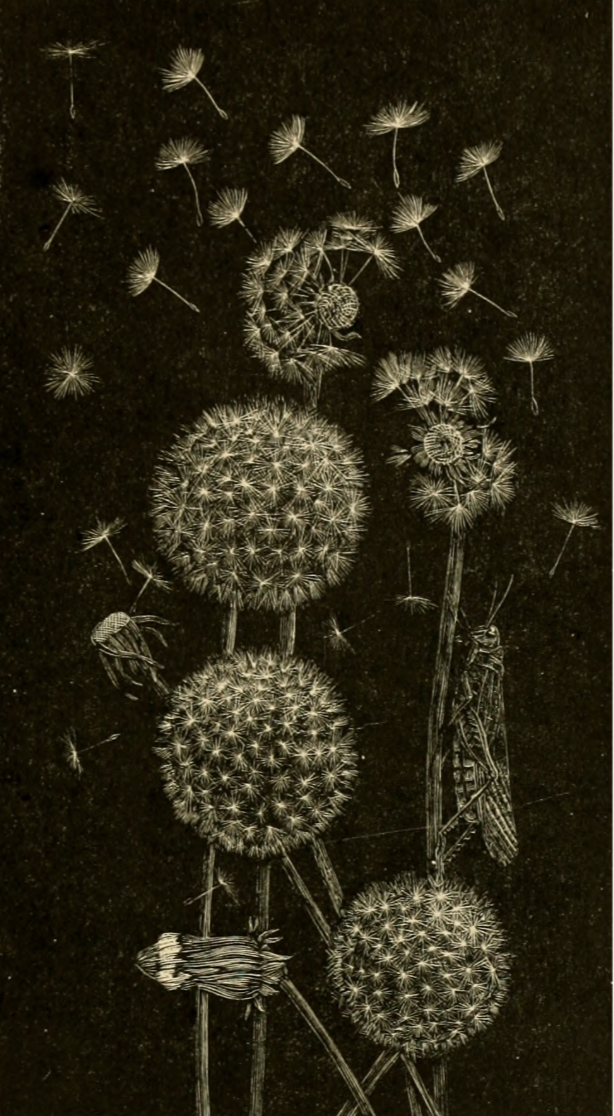

The interesting facts, well… To me, it was all, every bit of it, evocative and fascinating. But it was the surprises that came with the research that really pleased me. In THE LAST FOREVER, Tessa and her father are struggling to come to grips with the death of her mother. It’s a book about a girl, and her family; a boy and a dying plant; a town on a mission. It’s also a book about loss and safety and protection and the way that things that really matter can last. Writing always involves a little magic in the hard work; some unexpected gifts will get tossed your way. The gifts arrive via your own imagination, or from an experience you have during the course of the novel, or from the right insight at the right moment.

In THE LAST FOREVER, though, it was the actualities of the vault itself that kept on giving. Perfect nuggets presented themselves. One such perfect nugget arrived when I learned that in Longyearben, death is forbidden. It’s against the law. There, you’re not allowed to die. The law came about during the influenza pandemic of 1917-1920. Since the victims’ bodies did not decompose in those freezing temperatures, the virus inside of them stayed alive. So the officials there made a bold move. They simply declared that dying was not permitted in the town. It still isn’t. The cemetery has banned funerals, and anyone who is deathly ill must be shipped to the mainland. To Tessa, this vault, buried in the side of a frozen mountain, was not only the hidden location which might one day hold the seeds of her mother’s dying plant (along with 2.25 billion other life saving varieties), it was “a place where the town’s leader’s have said the one thing that’s needed saying for years: dying is wrong.”

Longyearben: Dying Not Allowed (Photo: Visit Svalbard)

One of the most meaningful things to me about the vault (and therefore, one of the most meaningful to Tessa) is that the seeds inside it are one of the most protected things on earth. First, there is the isolated, nearly inaccessible locale – 1,100 kilometers from the North Pole. And then there is the Svalbard archipelago itself, set in the distant and largely unknown Barents Sea. And then the island in the archipelago, a remote island, a barren piece of rock, really. And then the mountain. And then the ice, the years and years of ice. Then, of course, the guards, and the polar bears, and the blizzards to fight your way through. The layers of iron are next. And then the secret keys needed to open the dual blast-proof doors with their motion sensors, the two airlocks, the walls of steel-reinforced concrete one meter thick. Finally, the separate rooms. The containers. The specially wrapped packaging. And inside, the purpose of it all: the seeds.

Inside the vault. Layers of protection. (Photo: The Atlantic)

The level of protection and safety made real in the vault – it feels almost mystical, something impossible made possible. That it isn’t mystical at all but very real – it’s a powerful truth, I think. It’s an idea we need; at least, I do, and certainly Tessa did. In this world of change and anxiety, in our sometimes frighteningly precarious existence, it’s good to know that certain things, elemental ones, are made safe. Anything might happen, and yet those seeds, and the way to begin again, will last and last and last.