From the award-winning author of Honey, Baby, Sweetheart comes a gorgeous and fiercely feminist young adult novel. When a teen travels to Hawaii to track down her sperm donor father, she discovers the truth about him, about the sunken shipwreck that’s become his obsession, and most of all about herself.

Harper Proulx has lived her whole life with unanswered questions about her anonymous sperm donor father. She’s convinced that without knowing him, she can’t know herself. When a chance Instagram post connects Harper to a half sibling, that connection yields many more and ultimately leads Harper to uncover her father’s identity.

So, fresh from a painful breakup and still reeling with anxiety that reached a lifetime high during the pandemic, Harper joins her newfound half siblings on a voyage to Hawaii to face their father. The events of that summer, and the man they discover—a charismatic deep-sea diver obsessed with solving the mystery of a fragile sunken shipwreck—will force Harper to face some even bigger questions: Who is she? Is she her DNA, her experiences, her successes, her failures? Is she the things she loves—or the things she hates? Who she is in dark times? Who she might become after them?

The audiobook of THE EPIC STORY OF EVERY LIVING THING, narrated by Brittany Pressley, is just BEAUTIFUL. Listen to a snippet here:

“The world, and Harper in the world: this is the problem. The world is too big - it spits tornadoes and unleashes hurricanes, and it holds viruses that, in a matter of days, can wreck life as you know it. That’s hard to forget. And Harper is too small...”

Neptune’s Car, Mary, and Me

That old, strong DNA…

If you know me through my books or in my real life, you know I have a thing about the water. I’m not sure where it originally came from. My great uncle, who was a large figure in my growing up, was a merchant seaman, and my dad was in the Coast Guard, and coming from the San Francisco Bay Area and then later moving to Seattle may have contributed. Water feels like it’s in my DNA. I see the waters of Lake Washington right outside my windows, and I want to be in water, on water, or near water as much as I possibly can. When I looked through some photos for this essay, I realized a good two-thirds of mine, from childhood on, include a swimming pool, a lake, or an ocean.

As my readers also know, this love creeps into my books, too, nearly every one. One Great Lie takes place on an island in the waters surrounding Venice, and Essential Maps for the Lost features Lake Union in Seattle. Stay, and other novels, take place on fictional islands in the San Juans, in Washington State. I must have passed along that particular water-loving DNA to my children, too, because my son, Nick, is a nautical engineer and a sailor, and my daughter, Sam, is game to hop aboard any boat whenever possible. A huge bunch of my best family memories of us take place near water.

Oh, those great fun sunset sails on Obsession and Neptune’s Car, with thanks to Nick and Seattle Sailing.

I first became aware of Mary Patten’s story when my son was a sailboat captain for Sailing Seattle, which offers excursions and charters on their two seventy-foot yachts, Obsession and Neptune’s Car. On many weekends, Nick would also be racing on Neptune’s Car, and, as often as we could, we would hop on, as well, for an incredible sunset sail. During that time, I wondered about that curious name – Neptune’s Car – and its origins. What I read astounded me. I knew that sometime I would have to write about Mary, a young wife, a teenager, who not only became the first female to command a ship after her husband fell ill, she did it while eight months pregnant, after facing down a mutiny. She navigated and led the clipper ship, Neptune’s Car, its cargo and her crew around Cape Horn during horrendous gales, handled a violent and traitorous first mate and an incapable second mate, and brought her ship into the San Francisco Bay in second place in the race they were in.

That, my friends, is a girl who did what she had to do.

And, wait, did I mention that this took place in 1856? When there was a nationwide yellow fever epidemic, just before 1857, one of the greatest flu pandemics of all time?

You’d look serious, too, if you had to deal with a mutiny. (Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian)

Before I began The Epic Story of Every Living Thing, I was thinking a lot about doing what you have to do, hanging in there and coping and managing under difficult circumstances, because… Our pandemic. Mary had no idea what would be asked of her, and we had no idea what would be asked of us. But during that time, I took comfort in hearing stories about what people endured in the past. When I was tired and cranky and done with quarantine and uncertainties and fear, such stories put our own circumstances into much needed perspective. Mary fought a storm so brutal, that she wore the same clothes for fifty-two days. I fought boredom and irritation and, admittedly, wore the same sweatpants for several days in a row. Perspective. It was time to write Mary’s story, but not just Mary’s story. Harper’s story, too, and our story - one of unprecedented events in an unprecedented time.

While Mary’s unasked for adventure did not end with a missing ship in Molokini Crater, and while the journal entries are fictional, the events that Mary endured in the book are all true. What was going to happen at Molokini Crater: true as well. And what is also true, as you most likely know, as you most likely feel, are many of the things that Harper must struggle and reckon with that Mary never did – a near-constant message that we are in danger, set right beside the messages that we are helpless against it. Messages, of perfect people leading perfect lives, while ours… Isn’t. Messages that cause a riptide of anxiety and impossible expectations.

It’s a different kind a brutal storm. But make no mistake – both can pull you under. Both can wreck.

Firework Jellyfish (Photo: National Geographic)

The Epic Story of Every Living Thing is a story within a story: Mary’s within Harper’s, and Harper’s within Mary’s. As difficult as Mary’s life was, and as trying and confusing as Harper’s is, The Epic Story of Every Living Thing is, above all, a book about hope, wonder, and the human spirit. It’s about love, and the ways we show up for each other. And it’s about one of the best ways I know how to get through hard things - by remembering that we are all a story within a story: a human being with all of her or his frailties and power and beauty and possibilities, alive in a natural world with all its frailties and powers and beauty and possibilities.

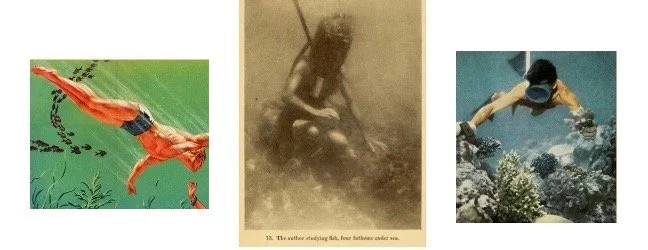

L. to R.: The legend of the bridal chamber at Florida’s Silver Springs as seen through glass bottom boats, undated; “The author studying fish, four fathoms under the sea”, Nonsuch Land of Water, 1932; Dahlak, with the Italian National Underwater Expedition in the Red Sea,1957

“The world, the real one, the one outside those squares? The messy, scary, unpredictable and hard one; the natural world, with its frightening power and powerful beauty; the human world, with its horrific wrongs and its moments of shining rightness, it’s worth it. The risk is worth it. The squares are nothing in comparison. Nothing.”

Coral rouge. Planches enluminées d'histoire naturelle, 1765; Life and Her Children: Glimpses of Animal Life from the Amoeba to the Insects, Arabella B. Buckley, 1883